For decades, lenses were sharpened in the big old brick building on the northeast corner of Second and Washington streets.

Starting in the late 19th century and continuing through the 20th into the early years of the 21st, that sharpening was integral to the quality industrial safety eyewear manufactured by the Willson family. From its inception in 1871 manufacturing optical glass to its evolution into the production of products as disparate as oxygen masks to fashion sunglasses, Willson went on to eventually be acquired by Dalloz Safety. Like so many domestic manufacturers, it was ultimately shuttered. The building was vacated in the spring of 2002.

But, in just three years, the once-bustling factory building took on a new identity as GoggleWorks Center for the Arts, to be recognized as one of the largest entities of its kind in the United States. Officials say it annually draws in excess of 250,000 visitors.

The main movers and shakers of that rebirth were industrialist Marlin Miller, the late businessman Irvin Cohen and the late department store magnate Albert R. Boscov, who collectively honed their vision into a dazzling reality.

But, over the course of the past 17 years, the lens through which that early vision occurred had grown a bit cloudy.

GoggleWorks, its name a salute to the building’s roots, became the anchor of what is known as Entertainment Square. Catacorner, the Reading Movies 11 and IMAX theatre was constructed. Just up Second Street fronting Penn, Reading Area Community College built the Miller Center for the Arts, a popular performance venue. GoggleWorks Apartments opened about a decade ago, a goal attained by Al Boscov’s tireless efforts and named for his good friend, the late state Senator Mike O’Pake.

But like Mike, Al Boscov has passed.

A life-sized statue in front of the parking garage that bears his name on the southeast corner, is a testimony to the bricks-and-mortar changes he brought to this busy intersection.

Overcoming Challenges

While the history is inspiring, a secure future for GoggleWorks requires an objective assessment of its operational past and present.

That’s where Levi Landis comes in. It was in 2016 that Landis, then in his early 30s, was appointed executive director of GoggleWorks, succeeding venerated educator Gust Zogas, now a board member, in the position.

With a younger-trending board and Landis, a new assessment of where GoggleWorks stood from both financial and programming operations occurred.

According to Landis, in 2015, GoggleWorks had a more than $300,000 operations loss. The financial challenges did not occur overnight. Through its first six years, the annual costs of operations were about $6 million. During his tenure, Zogas had the Herculean task of reducing that to around $1.5 million, and still there was the loss.

By the end of 2016, the institution had reached operational stability.

Currently, annual operations run about $2.5 million, Landis says.

Part of the operational challenges dealt with the variety of programming offered since 2005, much of it expanding over the years.

“In 2017 and 2018, we revamped our programs,” he says. “We threw out the Greek diner menu and narrowed them down to relevant programs.”

Landis and the board also considered the relevance of GoggleWorks to its immediate community.

Looking to the influence of Reading-based artists and endeavors like the Dear RDG podcast, a successful outreach to include the urban artists occurred – and continues.

In 2018, a program began to mentor career artists. Around the same time, the number of visits by Reading School District students increased.

Landis recalls one especially poignant question by a young pupil, who accidentally wandered into a vacant alley from a tour.

“She asked: ‘Why is there no art out here?’,” Landis recalls. “We knew she had hit on something important.”

Sweet Heroes to the Rescue

Sandy Solmon, the owner and founder of Sweet Street Desserts and a board member, took that thought to heart. She agreed that GoggleWorks likely didn’t seem overly approachable to its neighbors. Citing national trends that focused on cities with placemaking and art activating public spaces, she urged the board to act.

“She’s the hero of this program,” says Landis.

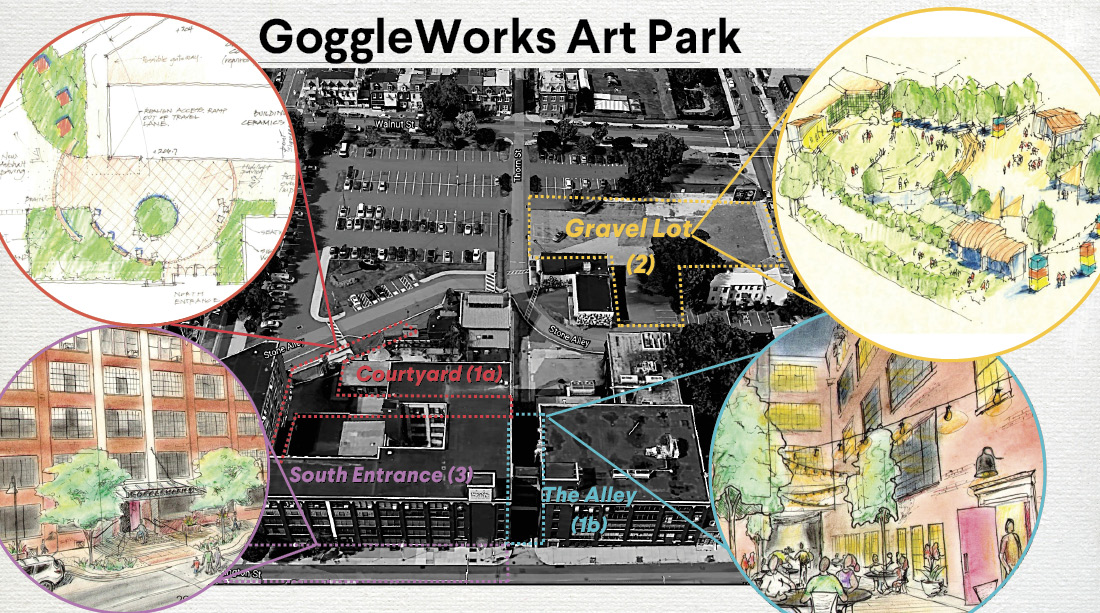

What the “program” evolved into is a three-phase effort to create an expansive and interactive Art Park on the grounds of GoggleWorks.

GoggleWorks’ interest and confidence in carrying out the project was aided by a $12-million endowment, The Fund for the Future of GoggleWorks, announced in February by board chair Tod Auman.

The Windgate Foundation contributed an astonishing $8.8 million. Windgate, which supports significant educational programs in contemporary craft and visual arts, initially gave a matching grant of $1 million in 2019 after GoggleWorks co-founder Marlin Miller, executive director Levi Landis, and board member Zogas visited the foundation at its headquarters in Little Rock, AR.

“After we reported success in matching the initial grant, Windgate announced they had been watching our work, and they wanted to give an additional $7.8 million,” says Zogas. “It’s a testament to the leadership of Levi, who championed this campaign and who collaborated with his great team and our community to make GoggleWorks more impactful and sustainable.”

Why would an Arkansas-based foundation be so interested in Reading’s GoggleWorks? Landis offered an explanation.

“The Windgate Foundation is a major force for transforming our world through the arts,” says Landis. There is a map in their headquarters with pins in all of the places where they have supported impactful work through arts and education. It looks like a scattered-rainbow block of colors. It’s a vibrant, tangible symbol of their widespread advocacy and leadership.”

Local philanthropists also stepped up to add to the endowment: Miller and his wife, Regina, donated $1 million; the Neag Foundation awarded a $500,000 grant; Pam and Peter Barbey contributed $500,000 through the Edwin Barbey Charitable Trust; and Zogas contributed $260,000 in the wake of the campaign kick-off contribution in that same amount by Dena and Victor Hammel. Shirley Boscov, sister-in-law of GoggleWorks co-founder Albert Boscov, pledged $50,000 to the fund. The funding allows GoggleWorks to sustain and maintain its current footprint but also showed leaders they could expand their mission outside of its factory walls.

Park it!

The groundwork for the outdoor art park – and GoggleWorks outreach to its neighbors – was set by getting the pulse of the neighbors. A grant from the Berks County Community Foundation enabled the hiring of a bilingual consultant who, along with staff members, canvassed the neighborhood.

They learned pretty much the obvious – many in the neighborhood were struggling to make ends meet and to care for their families. Visiting and getting involved in a nearby arts center was not a priority. Add to that another factor: for those undocumented, entering an established institution was taking a chance on being discovered.

At the same time, the Wyomissing Foundation created a GoggleWorks “U” task force, concentrating on getting feedback and suggestions from Sixth Ward business folks and residents who live in the “U” off Lauer’s Park bordered by N. Second, N. Third and Walnut streets.

The majority of respondents were supportive of GoggleWorks and asked for more outdoor, community activities including performing (dance, theatre) arts, as well as farm and/or food markets.

“Pretty much, they favored events where food and art can converge,” Landis says. “If art is about engaging the senses, how do we use food, which engages all five senses, music, and other programs as incentives to merge with art?”

The answer came with the concept of the “Art Park.” And it was not limited to just the grounds of GoggleWorks.

An active garden plot adjacent to Lauer’s Park Elementary School and long used as a learning site, was renamed GoggleWorks Gardens. Its goal: to use art to grow an appreciation for local food systems, learn farm skills and enjoy time with neighbors. Tiana Lopez, garden studio manager, leads that urban gardening effort.

At GoggleWorks itself, the expansion effort is designed to increase the amount of programming and green space.

Phased Out

Phase One, says Landis, set for this year, centers on what Landis calls “the asphalt jungle,” the entrance to the 145,000-square-foot building off N. Second Street.

The estimated $500,000 project would create a much greener (grass, plantings) courtyard and alleyway where “pop-up” exhibits and performances, especially those highlighting emerging artists, and other events could happen.

While the hope is to complete this in 2022, Covid-impacted supply chain issues and inflation have been unexpected and unwelcome challenges.

“Last year, our outdoor events attracted 20,000,” says Landis. A clear benefit is that neighbors can see the activity and join in, providing a great mix of locals and those traveling to the events from outside the city borders.

Phase Two is set to be a “creative commons.” Though Landis says it is premature to place an exact timeline or price tag on the endeavor, he did note the cost may exceed $7 million. The ambitious project may involve installing outdoor sculptures, constructing an amphitheater and designing a mini golf course, the latter which was a popular suggestion in community responses.

Construction would center in what is now the gravel parking lot/entrance off the 100 block of N. Third Street.

The amphitheater, he says, would have a retail facing…not a blank wall fronting the street.

Community the Priority

“This is key to community interaction with the arts,” says Landis. “We can envision a series of free concerts.”

The mini-golf would attract families to enjoy time together and become simultaneously exposed to the arts.

“If we can nail that part – highlighting sculpture with mini golf and marry programs of music and performance, that would be so great,” he says.

Phase Three would require the most critical public partner buy-in.

This phase fronts Washington Street and involves a re-configured southern approach/entrance to GoggleWorks. It calls for designated and safer bicycle and pedestrian access as well as a geographical and cultural connection to the new United Way of Berks County and Centro Hispano headquarters in the Albert Boscov Plaza parking garage on the southeast corner of Second and Washington streets.

Because Washington Street is a state road, any reconfiguration of traffic patterns must garner its approval. Hoped-for improvements include some on-street parking and other traffic-calming. The call for on-street parking along Washington Street is also being sought by local entrepreneurs who have or will be re-developing buildings from the 600 block westward.

In addition, a part of this phase involves an homage to Reading’s storied railroad history. There are still railroad tracks on GoggleWorks property that served the campus’ manufacturing predecessors, both Willson Safety Products and Stelwagon. Landis says one idea is to place a train car of some vintage which can be displayed as an art gallery and accessed by visitors.

Landis says “it’s way too early to budget” the cost of this final phase or to offer a project timeline.

Over the course of Landis’ tenure, the GoggleWorks team has also taken its show on the road. There have been more than 40 off-site visits, usually supporting established events such as West Reading’s Art on the Avenue or the nearby annual Juneteenth celebration in partnership with the NAACP.

A mobile furnace enables glass-blowing to be a part of these visits. The addition of an annealer or “glass cooler” will enable folks to take their creations home the same day.

At these events, GoggleWorks personnel have introduced a “Shatter Our Fears” endeavor. Individuals can freely write out their fears on scrolls over the course of a season and place these in an ornate glass vessel. That vessel and its contents are then destroyed by a giant “Hammer of Hope” and, in turn, another original glass piece is created.

“I think of this as how we redefine our city,” says Landis. “A thing of beauty emerges from our collective fears, and we create new opportunities together.”

With the planning, funding and implementation of these expansions and greening of GoggleWorks campus, the fears and concerns for its sustainability seem to be as shattered as that glass. As the institution nears its third decade, its Reading roots are only getting stronger.

Editor’s note: Donna Reed, a member of Reading City Council since 2002, has acted upon a number of legislative matters involving GoggleWorks Center for the Arts.