Midway through installing his exhibition at Kutztown’s New Arts Program in 1987, Keith Haring noticed something was missing.

The show was a homecoming for the renowned artist, born in Reading and raised in Kutztown, who achieved fame in New York City during the decade with his graffiti-inspired pop art. Things were certainly looking up for Haring, but at that moment he was looking down.

“He came to me and said that he felt he had to do something with the floor,” remembers James F.L. Carroll, New Arts Program’s founder and director. “And I said to go ahead and do it. After we talked, he went to Ace Hardware and picked up a quart of black latex paint, and he finished it in about an hour and a half.”

The exhibit is long gone, but the floor mural remains. A similar thing can be said about Haring: Though he tragically passed away in 1990 at the young age of 31 due to AIDS complications, his influence endures with new generations of fans continuing to discover his work.

And demand for Haring pieces shows no sign of easing. In late 2022, a small representation of the iconic Radiant Baby that Haring painted on the wall of his childhood home sold at auction for nearly $145,000.

“I can’t explain that,” Carroll says. “They’re just hungry for it, that’s all.”

“Keith from Kutztown”

Throughout much of the 1980s, Haring was art royalty. His works were exhibited across the globe; he created a mural on the Berlin Wall; he designed sets for MTV and he contributed a painting for the Live Aid concert in Philadelphia. Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono and Madonna were among his friends.

Though he spent his post-high school years outside of Berks County – first attending college

in Pittsburgh, then finding his new home in New York – Haring never forgot his roots, often introducing himself as “Keith from Kutztown” and keeping in touch with acquaintances in the area.

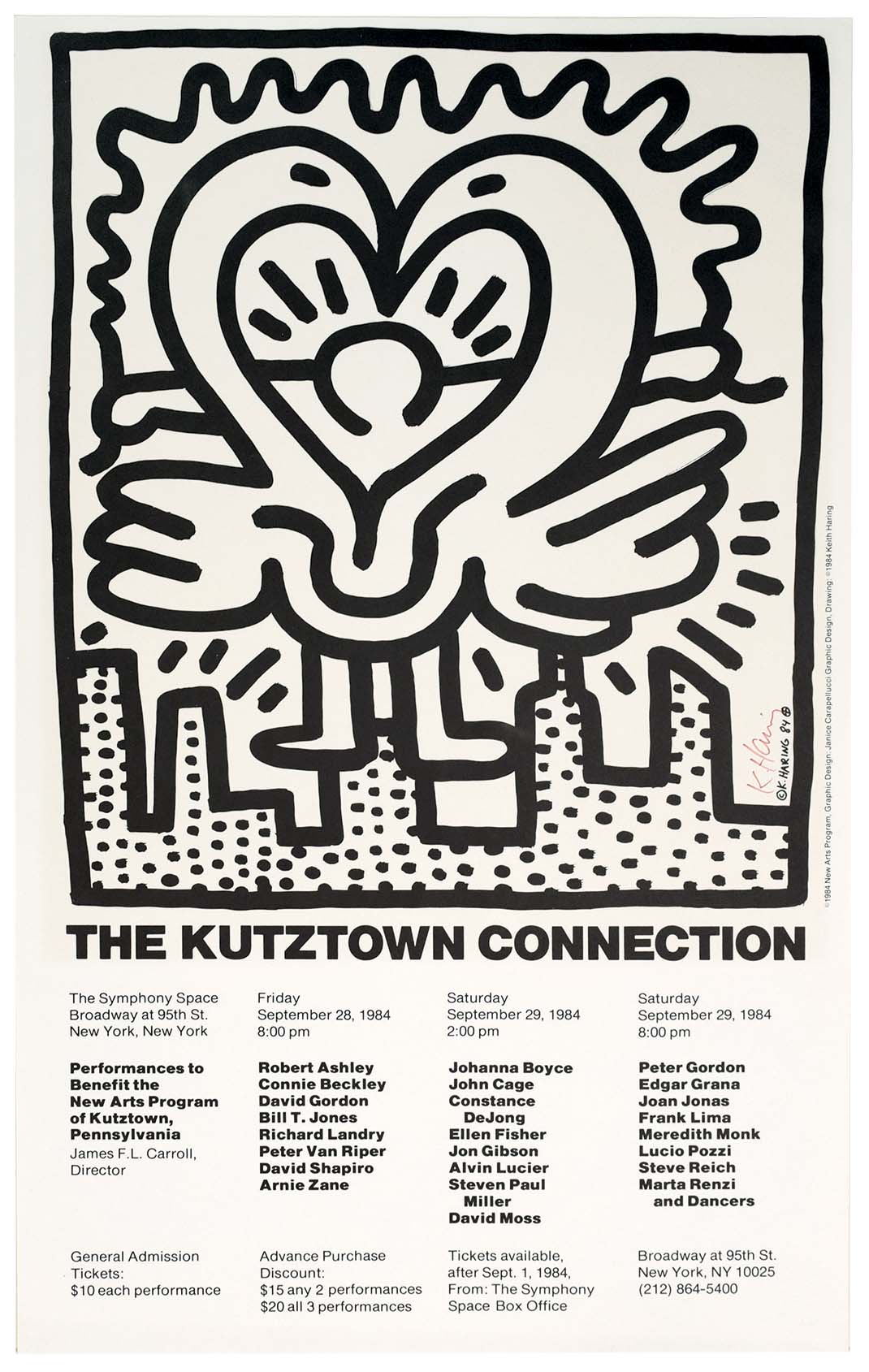

“I think one of the greatest things about him was that he was available,” says Carroll, who met Haring, then a quiet high school student, soon after New Arts launched in 1974.

“Most artists are not accessible to anybody other than themselves. If you asked him to do anything, he would do it if you had a reason for it. I called him a couple times and asked him to do a work to advertise something, and there was no question about it.”

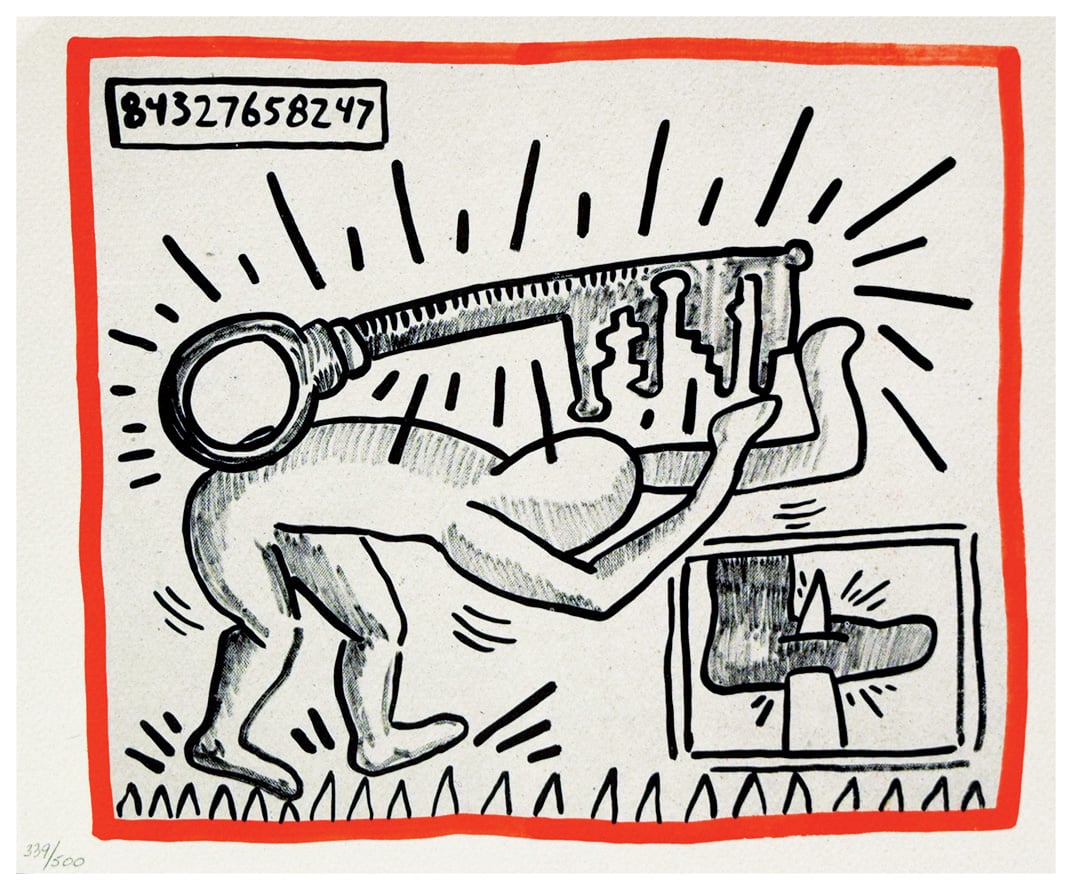

Haring’s accessibility permeated his work as well, which managed to balance critical and public acclaim — never an easy feat. He first gained prominence in New York City subway stations, creating chalk drawings of boldly outlined figures and dogs on blacked-out advertising spaces.

“Just because his work was accessible doesn’t mean that it wasn’t serious art, because it was,” says George Hatza, a freelance arts writer and the former entertainment editor of the Reading Eagle. “He was one of the first artists who wholeheartedly adopted an immersive art experience. When he started in the subways, that was no accident. That was his canvas. It was where people would see it and relate to it because it was about them. It was a brilliant decision.”

Hatza, who frequently commuted to New York City to attend theater performances during his professional career, remembers the first story he read about Haring in the New York Times and how floored he was when it mentioned Kutztown. After that, he became a devotee.

As his career progressed, Haring’s work became more political, warning against drug use and advocating for LGBTQ+ issues.

“I admired him for that,” Hatza says. “I thought it was gutsy. I think he wanted it out there, and I believe he thought it was time and that maybe his fame might in some way advance the movement, which not only was a smart thing to do but also a caring thing to do.”

Carroll was lucky enough to have seen his creative spark in action, stopping by New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art in the 1980s when Haring was installing a painting, which he recalls being about 30 feet tall and 20 feet wide.

“He was just about ready to start painting it, and I happened to be there when he started,” Carroll says. “Keith never made any pre-sketches. Whenever he made something, that was it. He first stood in front of it and moved his head, twisting it back and forth, and slowly walked in front of it. And then he took the paint, got on the ladder and did it. It was not something that he had to sketch out; it was in his mind.”

Not surprisingly, given where it was created, an urban aesthetic dominated his work. But his Berks upbringing percolated underneath.

“There is a deceptive simplicity to Haring’s figures that suggests both urban and rural influences,” Hatza says. “There’s something about them that looks not of New York, that looks from the wild. And maybe it goes back to his childhood because there’s something primitive about it, too.”

Bringing it All Back Home

Berks County lives in Haring’s work, and Haring’s work lives on in Berks County.

Along with the floor mural at New Arts Program, there is the Untitled (Figure Balancing on Dog) statue at Kutztown Park, a collection of chalkboard murals at the Kutztown Area Historical Society, a Nativity Scene drawing at St. John’s United Church of Christ in Kutztown – where his family were active members – and a permanent collection of works at Reading Public Museum, which hosted Haring’s immensely popular Journey of the Radiant Baby exhibit in 2006.

The newest Haring-related item in the county is a fitting tribute to the champion of public, accessible art. The Keith Haring Fitness Court is a limited edition outdoor center on Kutztown University’s campus, located a few blocks from where Haring grew up. Adorned with his brightly colored illustrations, the 1,120-square-foot installation contains 30 fitness pieces for the community to utilize. Users can admire his works while working out.

Sandra Green was instrumental in bringing the facility to the town where she served as mayor for more than a decade.

In 2021, the Keith Haring Foundation announced it was partnering with the National Fitness Campaign to create 10 limited edition fitness courts for which interested cities could apply. Meggan Kerber, then executive director of Berks Arts Council, alerted Green to the opportunity.

She knew she would be competing against exponentially larger cities, but Green, who now works as a community liaison at Kutztown Community Partnership and Kutztown University, felt strongly that Haring’s hometown deserved one. So she gave National Fitness Campaign a call.

“They said, ‘How big is your city,’” she recalls. “And I said, ‘The city is a borough, and the borough is about 5,000 residents.’ And there was dead silence. ‘But,’ I said, ‘Kutztown is the home of Keith Haring, and his parents and sister still live there.’ Again, dead silence. And they said, ‘Here’s the link to the application. Let us

know how we can help you.’ And I knew at that point we were going to be one of the 10.”

The $200,000 project, which was dedicated in October 2022, was built with the aid of several donations and $100,000 in state funding. On May 4, Haring’s birthday, an open fitness clinic was held at the court, followed by a Green-led walking tour spotlighting Haring’s artwork in town.

And there may be much more to come, with discussions afoot to display pieces he created during his time here.

“I talked to [Keith’s sister] Kay Haring, and the family has his early works from when he was in school, when he doodled on napkins and paper plates,” Green says. “And then you talk to relatives of his who were at picnics where he would draw on paper plates and napkins. I would love to find a spot to put that work somewhere here in town.”