It’s the age-old question: when does old age begin? It’s a question with no definitive answer; relative age can vary greatly from person to person. But with scientific advances allowing humans to live healthily for longer periods of time, 70 has become the new 50. Despite being of retirement age, three Berks County septuagenarians aren’t slowing down, continuing to draw upon their reservoir of knowledge and experience – to the region’s benefit.

Men in their late 70s, according to stereotype, are inclined to greet anyone stepping on their property with a throaty “Get off my lawn." Bill Rhodes, however, doesn’t mind visitors walking through his grass. The 76-year-old welcomes them. And he gets a lot, typically dozens on weekends. His “retirement oasis” on the corner of Third and Grand streets in Hamburg is impossible to miss.

Nestled alongside the plentiful plants in his yard is his collection of scrap metal artwork. He estimates there are 20 smaller pieces and about 10 larger ones, including a dragonfly perched on the front roof, an ostrich, a reflective giraffe, a dinosaur and a dragon. The biggest ones top 20 feet.

“I don’t mind if people walk through the yard; it’s here for everyone to see,” Rhodes says. “I get a lot of kids here. They’re fascinated with things like this.”

The pieces were crafted with a mélange of discarded parts: mixers, corkscrews, whisks, handles, springs, saw blades, a meat grinder, old wheels and gears, even a motorcycle exhaust. It’s a true art house. Even the sidewalk is painted blue.

“I have two 40-foot containers full of steel,” he says. “Our area is a mecca for flea markets and steel and things like that. There are people who go to yard sales every day, and on weekends they go to flea markets and sell their stuff. I have four people I go to and say, ‘I’m looking for this and that,’ and if they find it, I buy it from them.”

The origins of Rhodes’ creativity can be traced back to Three Mile Island. Originally interested in a career in architecture, he pivoted to welding, eventually landing a job as a welder at the Dauphin County nuclear power plant. When he wasn’t working on a project, he began to tinker with scrap metal. And he continued to tinker for much of the next half-century.

“I do it because I really enjoy doing it,” says Rhodes, who estimates he spends about three hours crafting on weekdays and at least five or six on weekends. “I don’t really make money on it. I sell very little. If somebody calls me and says they want something, or they wander into my yard and say, ‘Hey, I want to buy this. What do you want for it?’ then I’ll sell it. But I don’t really try to sell my work anywhere.”

His first piece, built 40 years ago, was an eagle crafted out of roofing copper for Cumberland Valley High School. The product of three months of work, it still rests on a podium inside the Mechanicsburg school. Much of his work has an abstract aesthetic to it, though he’s been transitioning into more defined pieces, “getting down to the nitty gritty of it,” he says.

Rhodes’ dwelling is a refurbished farmhouse from the early 1800s. When he bought it 20 years ago, it was uninhabitable, having been abandoned for nearly a decade. He’s painstakingly restored it, converting it to apartments, one of which he calls home. His repurpose-driven philosophy extends to the house’s interior, where everything has been given a new life.

“I’m decent at finding second uses for everything,” he says.

Rhodes retired from full-time work at a construction company, but they’ve hired him back part time. His four-day-a-week vocation finances his passion. And it will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

“I’m going to do this until I fall over dead,” he says, matter-of-factly. “I go to sleep thinking about work, I wake up thinking about building things.”

Karen Marsdale never thought about retirement amid her full-time professional career. Even when she neared the end of her two-decade-plus tenure at the Greater Reading Chamber Alliance, which included stints as senior vice president and president, it never entered her mind.

"I just couldn’t see myself with crossword puzzles or playing pickleball. And I don’t play golf," says Marsdale, 72. "I think it was probably because I enjoyed my job so fully. It was hard, and there were days when you didn’t want to get up and go to that 7:30 meeting, which the chamber was famous for. But I actually worked beyond age 65, and it was purely driven by the fact that I loved what I did."

The Oley Township resident finally said goodbye to full-time work in 2019 after her husband retired and her mother moved into the area. But not only did she have her post-retirement plan laid out, she was already heavily invested in it.

Soon after the turn of the millennium, a group of leaders seeking to make a difference in the community discovered a grassroots organization called Bridge of Hope, founded to help women with children who were homeless or at risk of homelessness. The Berks leaders opened the group’s second affiliate.

"I get a great sense of reward seeing somebody turn their life around," Marsdale says. "And I think we all should give back that which we’ve been blessed with as human beings."

After a decade, the team realized a void still existed, one that could be filled by opening a property dedicated to helping the women transition back into society. The group purchased and refurbished the former Mary’s Shelter building on Upland Avenue in Reading, located a few blocks from Alvernia University. Ties to Bridge of Hope were cut and Hannah’s Hope Ministries was born, named after a childless woman in the Old Testament whose prayers for a son were answered.

The program prepares moms to move into an independent environment within eight to 12 months. Each family in the transitional home has a private suite, but everyone gathers for dinner daily and each mother is expected to cook one of the meals each week.

“It’s a boot camp for success,” says Marsdale, the nonprofit’s acting director. “And we run the gamut from moms who are excellent cooks to young women who have never stepped foot in the kitchen. I say boot camp because there’s tough love, but the word ‘love’ goes with everything we do.”

Marsdale plans to stay in her current position for at least the next year as Hannah’s Hope bolsters its staffing, then she’ll likely transition into a different role. She spends about 20 to 30 hours a week working for the organization, but she doesn’t have standard hours outside of meetings. That freedom within the framework benefits her as well as Hannah’s Hope, and it’s something she believes other organizations should consider. Older workers accumulate an arsenal of expertise during their decades on the job, and if you don’t use it, you lose it.

“Many companies are finding that as people retire, all that knowledge goes missing,” she says. “You almost can’t make it up. Those of us in our 60s or 70s have so much knowledge that needs to be shared, and we need to keep sharing.”

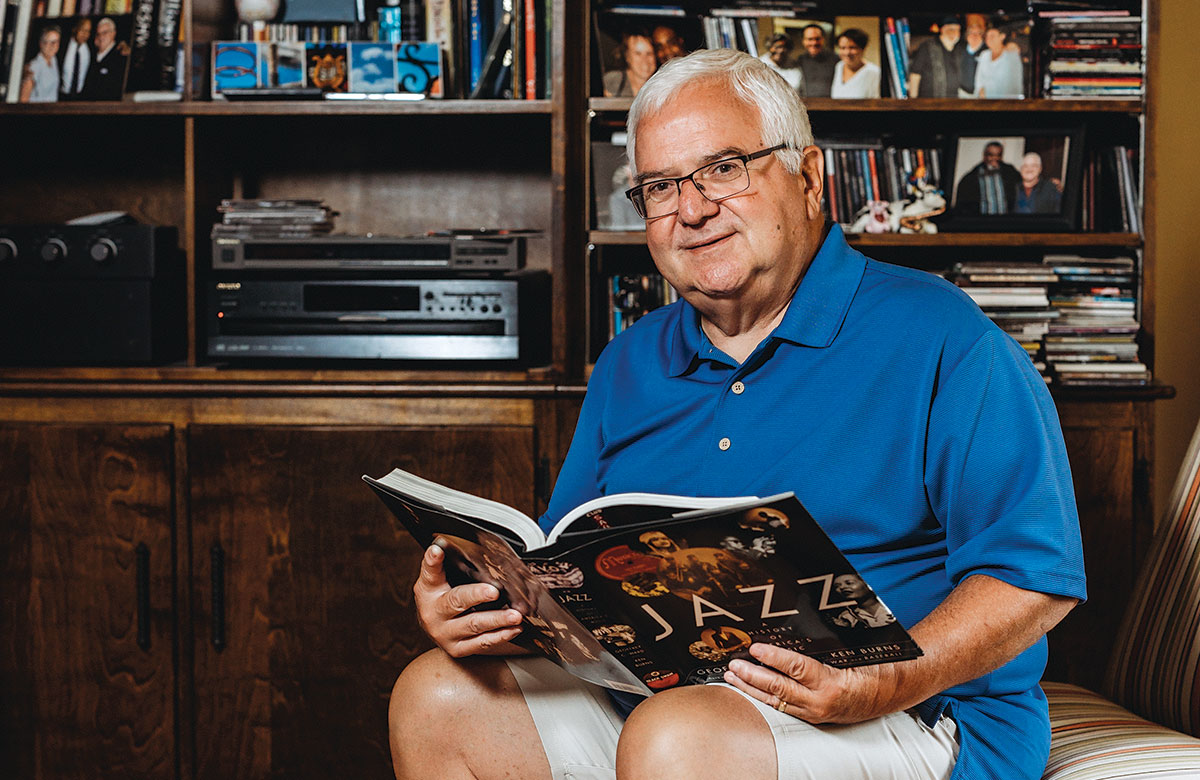

John Ernesto’s golden years have been filled with phone calls, scheduling, promotion and all that jazz. Literally.

Ernesto, 74, has led the Berks Jazz Fest for most of its existence. After guiding it through its turbulent early years, he helped to transform it into a globally recognized event that attracts roughly 40,000 fans annually. Debuting as a three-day festival in 1991, it expanded to six days in its sixth year and 10 days in its tenth. Next year’s event, running from March 24 through April 2, will be its 32nd iteration.

“I got involved because I was marketing director at the Reading Eagle,” says Ernesto, general manager of the festival since 1994. “They came to us about helping to launch it, so we got behind it, creating marketing plans and doing a special section.”

Turmoil nearly derailed the event soon after its successful launch. The executive director of festival organizer Berks Arts Council was fired after he was caught writing unauthorized checks. His replacement lasted only a year.

“So, I got involved the third year from a management standpoint,” Ernesto says. “And then the fourth year they asked me to take it over. I had never booked a band before, so I had to learn on the go. It’s been an amazing journey. Never did I think I’d still be doing it. And I’ve met so many amazing people doing this for the last 32 years, from artists to fans to people in the community.”

The roster of musicians who have performed at Berks Jazz Fest over the years is a who’s who of the genre: Wynton Marsalis, Stanley Clarke, George Duke, George Benson, the Manhattan Transfer, Grover Washington Jr., Bela Fleck & the Flecktones and hundreds of others. But perhaps none meant more to Ernesto than the Dave Brubeck Quartet.

“Dave Brubeck is the reason I got into listening to instrumental jazz back when I was in high school in the ’60s,” he says. “I remember going to Boscov’s and buying his vinyl album. And when my wife and I were backstage at his show, I said to myself, ‘Dave Brubeck is performing at a festival I’m involved with.’ That was one of those moments.”

Another one of those moments – memorable for a very different reason – occurred in March 2020. Weeks away from kicking off its 30th anniversary edition, the festival, like everything else in the world, was postponed due to COVID. It was delayed a second time in April 2021 before finally commencing in August of that year.

“When we got back, to see the joy on the fans’ faces was incredible,” he says. “And the artists were so happy to be back because they didn’t work for two years, and that gave me a lot of satisfaction knowing that we’re keeping this thing going all working together.”

The Cumru Township resident retired from the Reading Eagle in 2014 after a 49-year career. The newfound spare time allowed him to devote more energy to the Jazz Fest and its recently launched sister event, Reading Blues Fest. It’s a 365-day process, he says. Some days it’s a few phone calls, others it’s an eight-hour shift “fishing” for artists to squeeze into the schedule for the next event. And he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“It’s something that I have a great passion for and appreciation for, what it’s meant for me personally and what it’s meant to the community,” he says. “I never thought about age. I don’t think like I’m 74. I mean, there are days where I wake up and feel 74, but I just feel energized to be involved.

“I grew up in a community where I saw people like Albert Boscov stay very involved into their later years, and I always admired that. I’m taking it year by year. I want to be involved in some capacity as long as I’m able.”